Meltdown in Verona

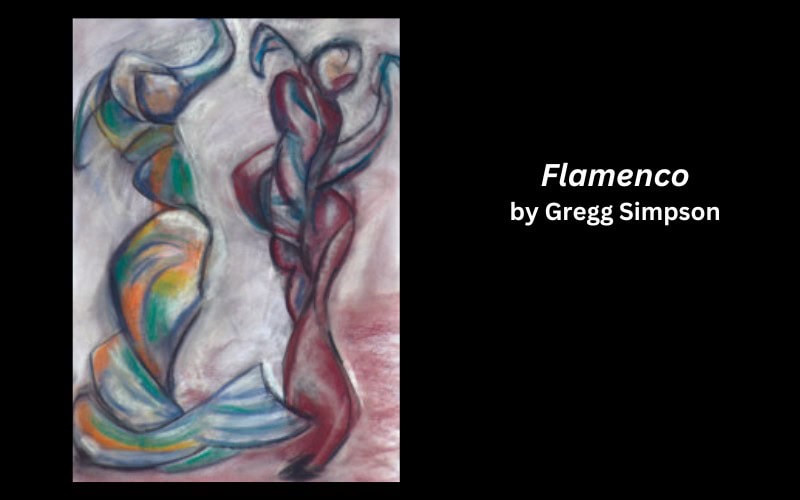

Meltdown in Verona is included in Pastel & Pen: Travels in Europe, a non-collaborative collaboration between Gregg Simpson and me. Gregg supplies the artwork, and I write the stories. I wrote this piece after one of the most fraught afternoons and evenings in my family’s travel history. Many years later, we can laugh about it, but at the time, our “Meltdown in Verona” threatened to tear us apart.

Two households, both alike in dignity / In fair Verona where we lay our scene. — Romeo & Juliet, William Shakespeare

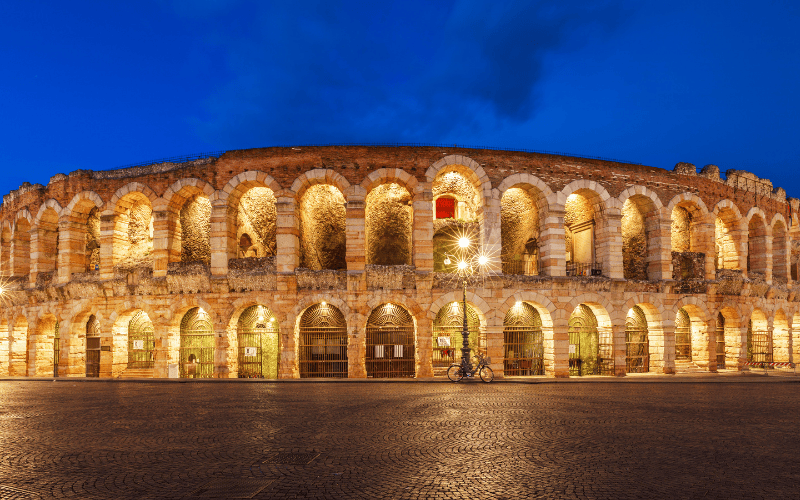

Almost encircled by a river, its buildings low and ancient, Verona looked as it had looked when Romeo rode hence to Mantua, when Juliet’s funeral procession snaked through the city gates, when the Montague boys crashed the Capulet banquet.

Fair Verona.

Yes, indeed it was. The tops of its brown weathered buildings shone warmly in the afternoon sun, a slight haze rose from the river, and a pale blue sky straight out of a Renaissance painting arched high overhead.

Several months earlier, an Internet search revealed that the Roman arena in Verona hosted an opera series. Although life-long music lovers, my husband, Gregg, and I had only recently discovered opera after attending a performance of Verdi’s La Traviata in an indoor theater with comfy seats and decent acoustics.

Imagine how much better, how much more authentic it would be to see a real opera performed in a real Roman amphitheater in a real Italian town! Could cultural tourism get any better?

I penetrated the clunky online ordering system and snagged the cheapest tickets for seats on unnumbered 2,000-year-old concrete steps. All that remained was to announce to friends who loved classical music that we were seeing Aida in the Roman arena at Verona and then to sit back and watch them turn green with envy.

At noon on a hot day in August, we drove into Verona and checked into our hotel. The opera wouldn’t start for nine hours, so our first stop had to be Juliet’s house. Juliet Capulet, that is. Her house, complete with balcony, gift shop, and statue with one bare breast glistening in the summer sun (don’t ask), must rank alongside the Green Gables of Anne fame on Canada’s Prince Edward Island as one of the most absurd, but lucrative, tourist attractions on Earth.

Romeo and Juliet had been my favorite play since I was a young teen like my daughter, and now it was hers. Gregg stayed behind at the hotel to watch the final hours of the Tour de France, and Julia and I set off for the Casa di Giulietta. Once there, we cheerfully handed over the entrance fee to visit a house belonging to a fictional character who, by definition, was a figment of someone’s imagination—a paper girl brought to life by a guy with a better than average knack for poetry.

Soon, we were climbing the stairs to the famous balcony and waiting while people took turns throwing out their O Romeo, Romeos. When our turn came, we stepped out onto the balcony and into the blinding flash of a camera.

The photographer gesticulated at me to nod, wave, and/or otherwise acknowledge that I’d buy the picture he’d taken. I decided to play it cool. Maybe, just maybe, I’d buy it, but I wasn’t letting him know that. No, Signor. If the picture flattered my good side, I’d consider parting with the cash. Otherwise, ciao baby.

I shrugged and turned away.

We wandered at leisure through the bare rooms of Juliet’s house. The brochure said that the house was genuinely old and had, allegedly, belonged to the Capello family who were the prototypes for the Capulets. There was also evidence that the building had served as a brothel, although the brochure didn’t indicate what evidence.

We descended to the courtyard and approached the photographer. By this time, we’d realized that the photos taken of people on Juliet’s balcony were printed onto white china mugs. Now there was a souvenir worth flying ten hours in cargo class to get. We loved tacky souvenirs on principle, and this was a souvenir that put the tack in tacky.

In vain, I searched for “our” mug, but alas, ‘twas not to be. When I asked the photographer, he looked surprised.

“I didn’t think you wanted it!”

Since I doubt that I’ll ever again stand on Ms. Capulet’s balcony, I must live my life to its conclusion unaccompanied by the photographic proof of my presence in Verona on that sultry afternoon in August.

Our visit to Verona that had started with such promise thus began a slow crawl to its ultimate destiny as a synonym for disaster in my family’s collective memory.

I soon cheered myself up with a bright idea. Why not walk over to the Roman arena and pick up our tickets for the opera? We could then return to the hotel, pick up Gregg, and enjoy a leisurely dinner at a quaint Veronese trattoria without needing to worry about queuing. Since it was 4 pm and the performance didn’t start until 9:15, the arena area would be deserted.

We arrived at the arena to find hundreds of people, most armed with cushions and newspapers, already stationed outside the various entrances. Fear twisted my stomach. We didn’t have numbered seats, which meant that we had to get in line right away or else …

After circumnavigating the arena (and it’s a big one), we found the ticket area. Not having anticipated that I’d be picking up the tickets early, I didn’t have my confirmation number.

“I need the number, Signora.”

“It’s at the hotel. But look, here’s the Visa I used to book the tickets.”

Grave headshakes, multiple keys pressed on the computer, soulful murmurings in rapid Italian.

“Please! People are already starting to line up!”

More key pressing, more murmurings, then a sharp intake of breath. It wasn’t looking good. The attendant squinted at me. “Name?”

I resisted the urge to tell her it was printed on the Visa and instead meekly spelled it out for her—all four letters.

Grimacing, she shook her head as if I’d gotten it wrong. I spelled it again.

A flurry of key pressing, murmurings rising in volume, another headshake.

“Please!”

Finally, with a sigh audible to everyone shuffling impatiently in the queue behind me, the attendant passed the tickets through the wicket and into my sweating palms.

“Where should we go?” I asked.

“Right now, go to entrance 65.”

“But my husband is at the hotel!”

“Get him right away,” she barked, as if I were short a few brain cells, which, as events transpired, was not an unreasonable assumption. “You must line up now to get a good seat.”

“Now?”

“Si. Don’t wait another minute!”

Oh. My. God.

Clutching $150 worth of unnumbered seats on 2,000-year-old arena steps in one hand and Julia in the other, I hailed a taxi. I could see the crowds around the arena expanding exponentially. By the time we returned, who knew how far back in line we’d be? Would we see anything at all?

We found Gregg lounging happily on the bed in the air-conditioned hotel room watching Tour de France cyclists roar down the Champs-Élysées toward victory.

“We’ve got to go right now!”

“What?”

“Now! The lady at the ticket booth said we needed to line up.”

“It’s not even 5 o’clock. And I’m watching the Tour de France!”

“We don’t have time! We have got to get in line! We can take turns going out for food.”

You’d have thought we were rushing to catch the last flight out before the Revolution.

With what seemed like agonizing slowness, Gregg got himself ready for the Great Experience to come. While his mood was not what I’d call enthusiastic, he was nevertheless moving. After all, we’d anticipated this evening for months. I knew he was as excited as I was to see a real opera in a real Roman arena in a real Italian town.

Less than an hour after I’d left the ticket booth and with the attendant’s exhortations sending poisoned darts into my brain, we arrived back at the arena. I led my family to Gate 65.

You have to visualize a Roman arena and its placement with relation to the pavement to understand the situation in which we found ourselves. Over the centuries, the base of the arena had sunk while the pavement had risen with the accumulated debris of the ages. Gregg peered over the railing into the ten-foot-deep trough.

“It looks like the pit of hell!”

“The ticket lady said we must get in line now.”

“I’m not spending the next four hours down there.”

“But…”

“Are you crazy?”

I looked down at the tops of heads bent over newspapers or chatting volubly with neighbors. The noise level would make a soprano wince, the temperature had to be in the mid-forties Celsius, and the space between bodies was a few inches at best. I tried to imagine standing down there with nothing to do, nothing to read, and nothing to eat for the next four hours.

Perhaps Gregg had a point.

“How about I get in line while you and Julia get something to eat?”

“That’ll take all of an hour and then what?”

“Well, you and Julia can get in line and I’ll get something to eat. We can take turns!”

Even to my ears, my Mister Rogers jollity sounded forced. To Gregg, it sounded insane.

What followed was not pretty and not for repeating. For the next four hours, the argument raged and cooled, flared, calmed, and raged again fanned by hunger and frustration until every hidden pocket of our relationship lay bare and exposed. After a month in Europe with barely a cross word, the strain had become too much. In one not-so-glorious eruption, we made up for it—and then some.

But as all arguments eventually do, ours petered out and with grim determination, we resolved to see the opera—and to enjoy it.

We staggered back to the arena to find that only the very worst of the cheap seats were still available. No matter. We’d paid for them and now fought for them and we were damn well going to love them.

After forking out the equivalent of $15 to rent three rock-hard cushions, we climbed and climbed and climbed up, up, up to the very brink of Roman heaven to find a meter’s worth of space ten rows from the top. While we were not exactly behind the stage, we had what could best be described as a sideways backside view.

A food vendor sold us drinks and desiccated ham sandwiches, and a libretto vendor sold us Aida Cliff notes packaged in a hot pink booklet with all the words in English, Italian, German, Dutch, and French. I settled down to read the synopsis. For those who don’t know, the gist of the opera is that Aida, a slave girl in ancient Egypt, falls in love and ends up willingly burying herself alive with her lover.

And we thought our relationship had its rough spots.

As the sky darkened to deep indigo, people-squashers (seriously) waded into the crowd and directed latecomers into two-inch wide spaces, exhorting the rest of us to squeeze together. At one point, a portly German tourist fell on top of Gregg and would have bounced all the way to the bottom of the arena if Gregg hadn’t grabbed his arm and hauled him upright.

Over the course of the final twenty minutes, a voice who spoke five languages informed us that the performance would begin in twenty minutes, fifteen minutes, ten minutes, five minutes, two minutes, one minute. The orchestra struck chords, the stage lights snapped off, and the entire arena burst into flame.

Almost every member of the 20,000-plus audience set fire to the wick of a birthday candle and then held it carefully aloft so the wax wouldn’t drip down the necks of the people in front. I didn’t want to appear rude by looking behind me, but the back of my neck prickled in anticipation.

The effect of so many thousands of candles flickering in the soft evening breeze was breathtaking. For a few moments, I felt transported. Here was a lifetime experience, one to share forever at dinner parties, to cherish with secret contented smiles in the years ahead. I looked over at Gregg and grinned, our argument forgotten in the magic of the moment.

And then the music began. At least I think it did. Aida, minuscule in a gold lamé halter top (I’m not kidding), appeared on stage, and we heard a thin stream of high notes and the faint whirring of violins. I strained forward and tried to look entranced.

The opera progressed as operas do. One person sang, another person sang, they sang together, one person stomped off, another entered, etc. Every so often, chorus members clad in floor-length blue and silver robes and with faces caked in bright blue makeup drifted on to the stage and sang.

The production designer was obviously heavily influenced by mid-1970s Olympics opening ceremonies.

At one point, several cast members leapt into canoes and paddled across a pool of water. Canoes? In Italy? Our Canadian souls appreciated the gesture, but really? Meanwhile, other cast members cavorted up and down the stage waving what looked like giant wedges of aluminum foil. I couldn’t quite get the connection with ancient Egypt, but I’m not too sophisticated in these matters.

Occasionally, the acoustics improved, and we’d hear a snippet of an aria. At this point, the two women behind us started singing. Now, I have no objection to anyone expressing themselves in their own country and in their own language, but it’s difficult to retain benevolence for people who drown out the professionals with voices that, to be charitable, were really, really bad.

Who knew that outdoor opera in Italy was a participation sport? It was sort of like soccer without the sweat.

By the end of the first act, our cramped muscles and concrete-hardened butts were screaming.

“My back’s really sore!” Gregg moaned.

“I know,” I replied tightly. “Let’s go.”

“Really?” Julia looked up from the libretto. “I like it!”

Now, there was a surprise. Despite our best efforts, Julia had resisted the lure of classical music, and opera in particular. She’d consented, grudgingly, to see Aida but had vowed not to enjoy it, yet here she was asking to stay while we could hardly wait to leave. I wavered for a few seconds, not wanting to nip this new-found interest in the bud.

But then I looked at the agonized set of Gregg’s jaw. He had a pathological hatred of crowds and, as a very tall person, dreaded being cramped.

It was time—finally—to admit defeat.

We stood up and began to edge along the row.

“Scusi, scusi, oh, sorry, pardon me, scusi, ouch, sorry, scusi, prego, scusi …”

The row went on forever. I trampled toes, elicited angry gasps, felt my face burn with embarrassment. We got to the end of the row only to find…nothing. There was no way out. No aisle. Nothing. Just row upon row upon row of tightly packed opera lovers all watching the stage.

The stage? Oh no! The lights came up and the performance began again. What we thought had been the start of intermission had only been a two-minute pause.

“Scusi, scusi, oh, sorry, pardon me, scusi, ouch, sorry, scusi, prego, scusi …”

We reached our cushions and sank down to the accompaniment of various disapproving clucks and whispered Italian curses.

Act II was excruciating, but at least it ended with the famous triumphal march loud enough to drown out the singing women behind us. The lights went up and the five-language voice promised a 30-minute intermission. From out of nowhere emerged coolers, wine glasses, and even little tablecloths as audience members settled down for a good half-time opera supper.

We resolved on escape. But to do so, we’d have to step in the tiny gaps between people from row to row in a near vertical descent.

“Scusi, scusi, oh, sorry, pardon me, scusi, ouch, sorry, scusi, prego, scusi …”

One English woman seated next to a side railing that we—and others before us—had decided denoted a thoroughfare, hit her breaking point just as I reached her. As I gently tried to squeeze between her and the railing, she shifted her considerable bulk and left me with two equally dire choices.

I could stand still and never see my family again or I could step on the woman’s thigh. I chose the latter.

“Do you mind?” she squawked.

And then she punched me. Hard. The woman could have tried out for England’s national boxing team—heavyweight division.

“I’m doing my best!” I wailed, as my other foot landed on her ankle. I heard bone crunch and then I was free and running, expecting at any moment to be tackled to the dirt. I rounded the corner into the stairwell and almost collided with an attendant. He motioned toward my hand with his stamp. “Returning?”

He’s lucky I didn’t kill him.

Outside in the cool, uncrowded evening air, we walked past an open tent being used as a dressing room for the male chorus. Most of the men were naked except for tight blue leotards stripped to the waist and in some cases knees and leaving nothing to the imagination.

Cigarettes hung from bright blue faces, bare bottoms and sweat-slicked thighs glinted in the dusk, eyes stared with gloomy resignation.

Gregg wrapped one arm around my shoulders, I took Julia’s hand, and together we walked away from the arena and into the floodlit streets of fair Verona.

About the artwork: Gregg had just finished creating Fin du Tour de France when Julia and I burst into the hotel room and dragged him out to the Verona arena and the start of an evening that became a family legend—and not in a good way, although we laugh about it now. The pastel celebrates the race to the finish line on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, French flags flying.

Enjoyed Meltdown in Verona?

Download Pastel & Pen: Travels in Europe for more of my stories inspired by travels in Europe and by the pastel drawings created by Gregg Simpson.