Enjoying the Museum of English Rural Life in Reading, England

Artsy Traveler contains affiliate links for products and services I personally use and can happily recommend. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Please read the Disclosure for more information. If you make a purchase through these links, at no additional cost to you, Artsy Traveler earns a small commission. Thank you!

This must-see museum of thoughtfully curated exhibits showcases the history of life in rural England.

Eight galleries and an impressive open storage area present artifacts and commentary related to the traditions and challenges related to food production in the English countryside.

I spent a wonderful afternoon at this museum in Reading with associate director Isabel Hughes, who graciously answered my many questions about the museum and then took me on a guided tour.

This place is a real Artsy Traveler find! And fair warning: this is a LONG post because there is just so much to write about.

Some Background

I lived in Reading for three years a few decades ago. During that time, I attended the University of Reading where I earned my BA in English Language and Literature.

I hadn’t returned to Reading since I graduated, so on a recent trip to England from my home near Vancouver, BC, I decided to make Reading my first stop after flying to Heathrow from Vancouver.

I wasn’t sure what I planned to do during my one afternoon in Reading. I googled museums and discovered the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL) run by my alma mater, the University of Reading.

I had never heard of MERL, although Isabel told me the museum was established in 1951 and did indeed exist when I attended the university in the 1970s.

In 2004, the museum moved to its spacious new digs in the former St. Andrew’s Hall, one of the student residences that was around during my time at the university.

Since its expansion, MERL has established itself as one of the United Kingdom’s premier destinations at which to learn about English rural life.

Why I Wanted to Visit the Museum of English Rural Life

I decided to visit MERL for two reasons.

First, it’s a niche museum and as such is a perfect candidate for featuring on Artsy Traveler.

Although I often write about blockbuster museums such as the Rijksmuseum, National Gallery of London, and the Uffizi, my heart beats particularly fast when I discover an off-the-beaten-track museum that my readers may not know about, and that fits with my interests.

The second reason I wanted to visit is because one of my novels titled Hidden Voices is partially set in Devon in the 1880s.

Eliza, my main character, must move with her family from a bucolic rural life in Devon to the “dark, satanic mills” of northern England where most of the novel takes place. In the scenes set in Devon, I wanted to sprinkle in a few more details about rural life that I hoped to find at MERL.

And I wasn’t disappointed! This extensive museum dedicated to farming practices and rural life is a hidden gem—and admission is free or by donation.

Arrival at the Museum of English Rural Life

A few hours prior to visiting MERL, I land at Heathrow after a smooth eight-hour flight from Vancouver. Twenty minutes after deplaning, I’m standing, phone in hand, searching for my Uber.

Most of that time has been taken up with long, long walks through long, long corridors, many rides up and down long escalators and a two-minute wait to go through the electronic customs kiosk.

Since my flight has arrived an hour early, I take the Uber to my hotel before heading to the museum. I’m staying at the Hotel Malmaison (#1 on the map) in downtown Reading, which I highly recommend. After freshening up, I decide to walk the 22 minutes from the hotel to MERL (#2). Here’s a map of Reading:

Along the way, I expect to take a few jaunts down memory lane, but alas, it isn’t to be. Nothing looks the same as I remember from the 1970s—not even close. The Reading skyline bristles with new buildings designed by architects who likely hadn’t been born when I was studying at the university.

When I lived in Reading, there was hardly anywhere to get coffee, much less enjoy a meal. We existed on copious amounts of strong tea; coffee bars were unheard of. And as for eating out, it just wasn’t done, or at least very rarely. Now, every other establishment in Reading serves food, or so it seems as I stroll past the cafes and restaurants in the downtown area.

Along the way, I cross over the Kennet-Avon canal which looks serene and well-groomed in the late August sunshine.

When I arrive at MERL, associate director Isabel Hughes meets me and, over a very welcome cup of tea, we start our chat.

The Interview

Here’s a summary of my interview with Isabel Hughes, associate director of the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL) at the University of Reading in England.

Enjoying this post? Subscribe to Artsy Traveler to Receive Valuable Travel Tips and Your FREE Guide: 25 Must-Do Artsy Traveler Experiences in Europe for 2025

Carol

What is the purpose of the Museum of English Rural Life?

Isabel

The purpose of the museum is to present exhibits and objects that help visitors understand the human side of English rural life: the production of food, farming practices since the 19th century, and the changing countryside. We like to present the human side of rural life and really celebrate working people since the vast majority of people in the 19th century and into the 20th century either worked on the land or in mills, or were servants.

Farming practices began to change in the late 19th century because of the agricultural depression caused by wheat production in Canada.

Carol

That’s very interesting because in my novel Mill Song, my main character’s family moves from Devon because there is no more farm labor work for the men. I thought it was because of mechanization that jobs became scarce, but there was also an agricultural depression. It’s interesting that Canada was to blame! A lot of people, including many of my ancestors, emigrated from a rural life in the West Country to Canada during the 19th century.

Isabel

MERL was started by the Agriculture Department at the University of Reading in 1951. World War II had ended and there was a push to make agriculture more self-sufficient and productive with the use of insecticides and the development of large farms. But as a result, traditional farming practices were being lost.

The founders of the museum realized this and decided to collect items such as old wagons and hand tools. They went to agricultural shows and talked to farmers, and acquired examples of traditional crafts such as basketry, woodworking, and bodging (making things such as brooms and chairs out of unseasoned green wood).

In 2004, the museum moved to its present location in the former St. Andrew’s Hall of residence, helped in part by funding from Alfred Palmer, a well-known Reading businessperson.

Carol

I well remember taking my exams at Reading University in the Palmer Building! He was quite the benefactor.

What is your number one recommendation for touring the museum?

Isabel

We like people to have a wander and see it all. The huge collection of wagons is particularly impressive. We have wagons from almost every county in England.

People can explore the eight galleries and then go upstairs to view our open storage of the thousands of items the museum has collected over the years.

Attached to each artifact is a luggage label; these were the original labels affixed when the artifact was acquired by the museum.

Another thing that we want people to notice is the textile wall hanging created for the Countryside Pavilion at the Festival of Britain in 1951. It was one of several we acquired. The one on display depicts Cheshire and cheese production.

Carol

What is your favorite exhibit and why?

Isabel

I think my favorite is a pitchfork that was grown in a hedgerow. A branch growing off the shrub was nurtured until it was just the right size and shape for a pitchfork.

It’s made by nature but guided by hand.

Carol

What are some of the hidden gems that visitors should check out at MERL?

Isabel

The display of friendly society pole heads is intriguing. A friendly society was a cooperative that workers bought into. If they had a rough time, then the cooperative could help to support them. The pole heads were elaborately carved and resembled pub signs. They were carried in processions such as church parades.

Carol

Is this place the only rural museum in England?

Isabel

It is one of the earliest museums but not the only one. There is a rural museum network that includes small community museums. Other large museums like MERL are the National Museum of Rural Life in Scotland and the St. Fagan’s National Museum of History in Wales. There is also the Weald and Downland Living Museum near Chichester, which is where Repair Shop is filmed. We like to think of MERL as the national rural museum for England, but it is not, officially.

Carol

What is the most popular gift shop item?

Isabel

We’ve had images from the wall hangings turned into merchandise such as mugs, pencil cases, notebooks, tea towels and bags. We also have tea towels depicting engineering drawings of farm machinery, which are very popular with enthusiasts who are interested in recreating rural farm machinery.

Carol

Are any new exhibits planned?

Isabel

We have quite a few artifacts related to the Roma people that are often not labeled as such. These include photographs of people working the land, and a gypsy wagon. We are starting to re-label these artifacts to feature the history of the Roma people in the English countryside.

Carol

Anything else you’d like to share?

Isabel

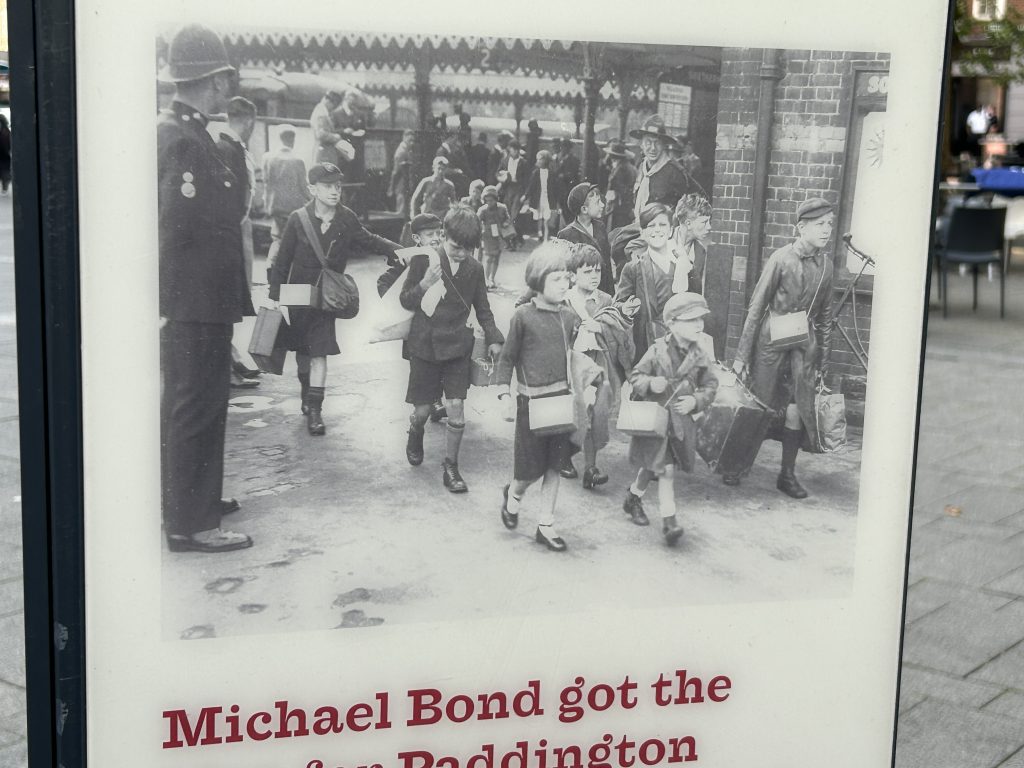

At MERL, we have an extensive library and archives containing a wealth of stories. Of particular note is our archive of letters that children evacuees during World War II sent to their parents when they were evacuated from the cities to the countryside. Reading was one of the hubs for evacuee children. Some of the letters were positive, depicting the experience as active and fun, while others were from children who were upset and even mistreated.

The labels affixed to the children when they were put on the train to go into the countryside inspired Michael Bond to write the Paddington Bear books in the 1950s.

Touring the Museum Galleries

After our chat, Isabel takes me around the museum. Seeing it after talking with her really brings it to life. Throughout the galleries are interactive activities for children. MERL has an active school program and welcomes over 50,000 visitors a year, likely a good proportion of them families.

I love the sheep clad in an Aran sweater in the first main gallery.

The size of MERL surprises me. The galleries go on forever, each one more chock-a-block with artifacts than the last. You can spend a lot of time here!

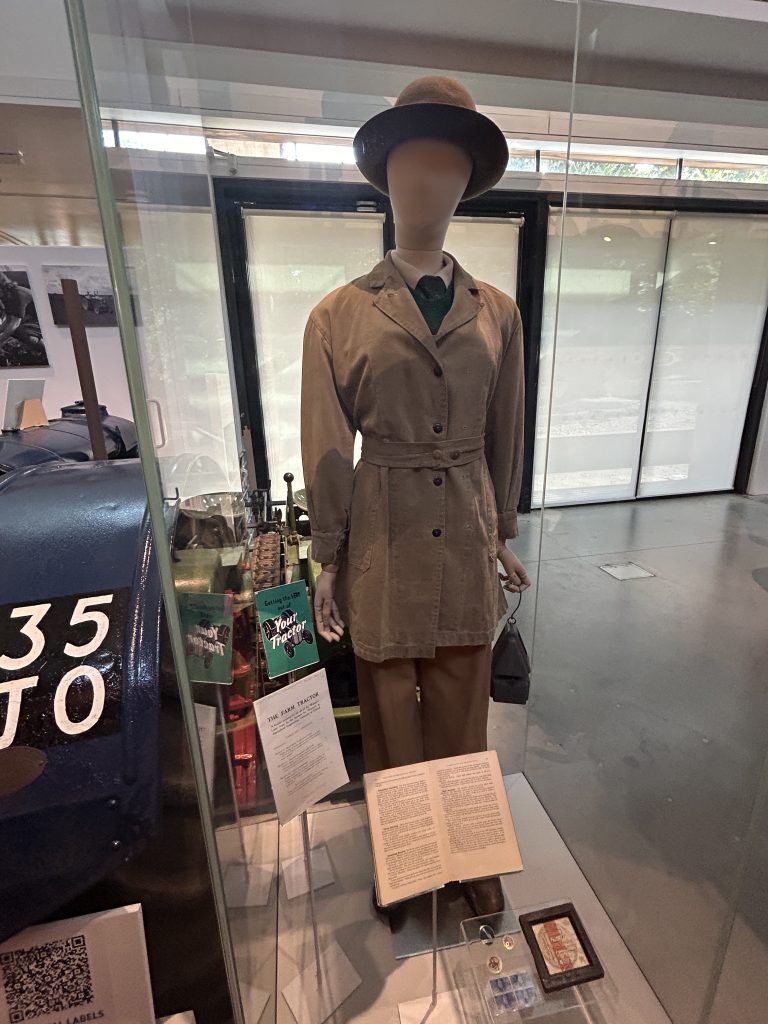

Land Girls

I’m particularly taken by the collection of objects and photographs related to the Land Girls—young women who worked on the farms during World War II. Here are photographs of several Land Girls and the uniform they wore.

The Land Girls experience inspired Land Girls, a British TV series available on Netflix.

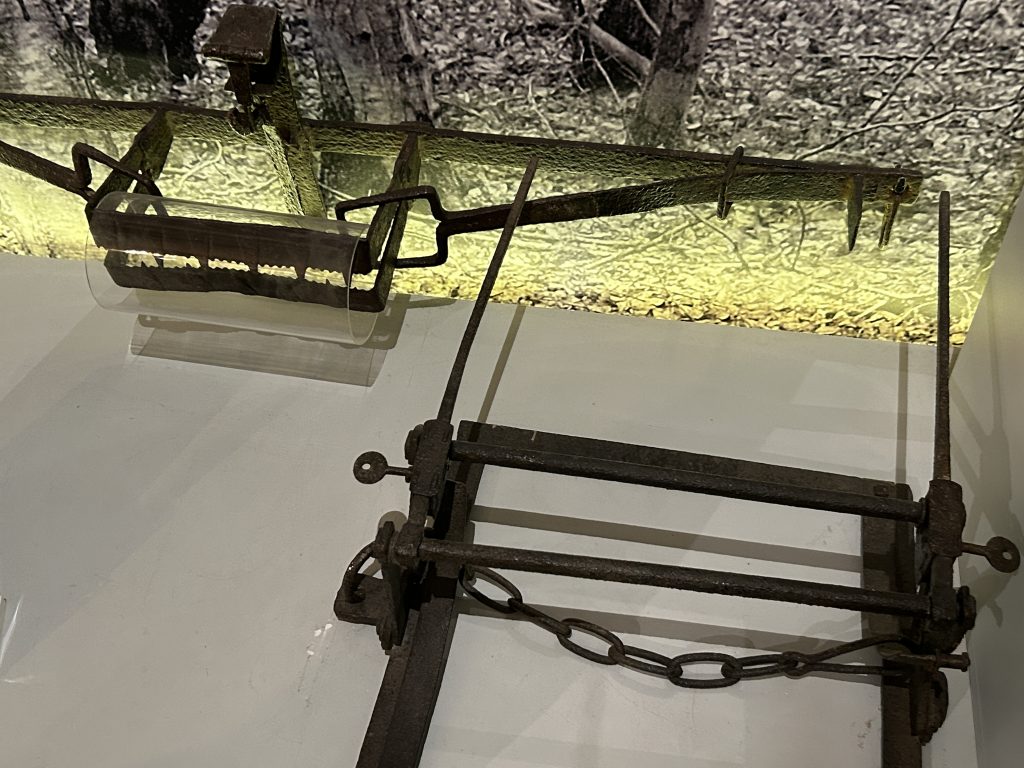

Traps

A sobering exhibit features various traps—both for animals and people. The two human traps are particularly horrifying. Anyone caught in one would likely die a very slow and painful death. These traps were placed to prevent poaching.

We spend almost an hour roaming through the galleries and viewing the open storage collections on the first floor. I’m very impressed with both the size and the quality of the exhibits and am reminded how, in another life, I would have loved to have been a museum curator.

But being a novelist and travel blogger is also good—and MERL ticks the boxes on both fronts. I’m finding plenty of inspiration for the country scenes in Mill Song. The open storage collection of smocks, many beautifully embellished with traditional smocking, reminds me of what some of my characters may have worn. I can also imagine my main character wearing a bonnet, such as the ones displayed, while she helped with the harvest.

New Inspiration

To my delight, MERL sparks inspiration for a new novel based around the story of two evacuees in World War II. After my meeting with Isabel, I scribble several pages of notes about possible characters and plots. It looks like I’m going to have to return to MERL to comb through their extensive archive of letters written by evacuees during World War II.

I can only imagine what treasures await.

As the museum gets set to close, Isabel and I pose for a photo, I purchase a notebook that shows a detail from the Cheshire wall hanging, and say my good-byes.

I walk back to my hotel, enjoy an excellent dinner, and then, finally, turn the lights out at 9. My first day in the UK has been a success.

Exploring the Area

Here are some GetYourGuide tours in southern England. Most depart from London.

Conclusion

The Museum of English Rural Life is a specialty museum with broad appeal. Touring a museum dedicated to how food was produced back in the day reminds us of our rural roots–and everyone eats food! No matter where you come from, chances are good that at least a few of your ancestors had something to do with agriculture.

The opening times of Museum of English Rural Life are from 10am to 5pm daily and entrance is free. It is located at 6 Redlands Road in Reading, Berkshire. The museum’s extensive website showcases its many exhibits.

Have you visited this museum or another like it? Share your comments and suggestions in the comments below.

Fascinating interview and the galleries look great. Love the pitchfork – ‘made by nature, guided by hand’. And I didn’t realise the impact of the Canada wheat industry either. So much of interest – I must visit!

The Weald & Downland Living Museum is certainly a very worthwhile trip – I would suggest it is a quite different approach and experience to MERL.

Thanks, Martin! The MERL was a revelation to me. If you’re at all interested in rural history, it’s a must-see! On my next trip to the UK, I’ll put a visit to the Weald and Downland Living Museum on my list! Hope you are well!